| Organising principle | Source file | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| One function | tidyr/R/uncount.R | Defines exactly one function, uncount(), that’s not particulary large, but doesn’t fit naturally into any other .R file |

| Main function plus helpers | tidyr/R/separate.R | Defines the user-facing separate() (an S3 generic), a data.frame method, and private helpers |

| Family of functions | tidyr/R/rectangle.R | Defines a family of functions for “rectangling” nested lists (hoist() and the unnest() functions), all documented together in a big help topic, plus private helpers |

6 R code

The first principle of making a package is that all R code goes in the R/ directory. In this chapter, you’ll learn about organising your functions into files, maintaining a consistent style, and recognizing the stricter requirements for functions in a package (versus in a script). We’ll also remind you of the fundamental workflows for test-driving and formally checking an in-development package: load_all(), test(), and check().

6.1 Organise functions into files

The only hard rule is that your package must store its function definitions in R scripts, i.e. files with extension .R, that live in the R/ directory1. However, a few more conventions can make the source code of your package easier to navigate and relieve you of re-answering “How should I name this?” each time you create a new file. The Tidyverse Style Guide offers some general advice about file names and also advice that specifically applies to files in a package. We expand on this here.

The file name should be meaningful and convey which functions are defined within. While you’re free to arrange functions into files as you wish, the two extremes are bad: don’t put all functions into one file and don’t put each function into its own separate file. This advice should inform your general policy, but there are exceptions to every rule. If a specific function is very large or has lots of documentation, it can make sense to give it its own file, named after the function. More often, a single .R file will contain multiple function definitions: such as a main function and its supporting helpers, a family of related functions, or some combination of the two.

Table 6.1 presents some examples from the actual source of the tidyr package at version 1.1.2. There are some departures from the hard-and-fast rules given above, which illustrates that there’s a lot of room for judgment here.

Another file you often see in the wild is R/utils.R. This is a common place to define small utilities that are used inside multiple package functions. Since they serve as helpers to multiple functions, placing them in R/utils.R makes them easier to re-discover when you return to your package after a long break.

Bob Rudis assembled a collection of such files and did some analysis in the post Dissecting R Package “Utility Belts”.

If it’s very hard to predict which file a function lives in, that suggests it’s time to separate your functions into more files or reconsider how you are naming your functions and/or files.

The organisation of functions within files is less important in RStudio, which offers two ways to jump to the definition of a function:

-

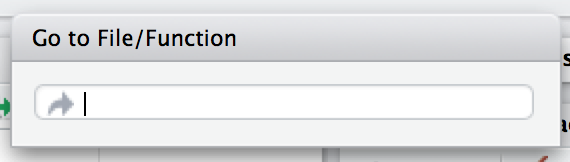

Press Ctrl +

.(the period) to bring up the Go to File/Function tool, as shown in Figure 6.1, then start typing the name. Keep typing to narrow the list and eventually pick a function (or file) to visit. This works for both functions and files in your project.

Figure 6.1: Go to File/Function in RStudio. With your cursor in a function name or with a function name selected, press F2. This works for functions defined in your package or in another package.

After navigating to a function with one of these methods, return to where you started by clicking the back arrow at the top-left of the editor (![]() ) or by pressing Ctrl + F9 (Windows & Linux) or Cmd + F9 (macOS).

) or by pressing Ctrl + F9 (Windows & Linux) or Cmd + F9 (macOS).

6.2 Fast feedback via load_all()

As you add or modify functions defined in files below R/, you will naturally want to try them out. We want to reiterate our strong recommendation to use devtools::load_all() to make them available for interactive exploration instead of, for example, source()ing files below R/. The main coverage of load_all() is in Section 4.4 and load_all() also shows up as one of the natural development tasks in Section 1.8. The importance of load_all() in the testthat workflow is explained in Section 14.2.5. Compared to the alternatives, load_all() helps you to iterate more quickly and provides an excellent approximation to the namespace regime of an installed package.

6.3 Code style

We recommend following the tidyverse style guide (https://style.tidyverse.org), which goes into much more detail than we can here. Its format also allows it to be a more dynamic document than this book.

Although the style guide explains the “what” and the “why”, another important decision is how to enforce a specific code style. For this we recommend the styler package (https://styler.r-lib.org); its default behaviour enforces the tidyverse style guide. There are many ways to apply styler to your code, depending on the context:

-

styler::style_pkg()restyles an entire R package. -

styler::style_dir()restyles all files in a directory. -

usethis::use_tidy_style()is wrapper that applies one of the above functions depending on whether the current project is an R package or not. -

styler::style_file()restyles a single file. -

styler::style_text()restyles a character vector.

When styler is installed, the RStudio Addins menu will offer several additional ways to style code:

- the active selection

- the active file

- the active package

If you don’t use Git or another version control system, applying a function like styler::style_pkg() is nerve-wracking and somewhat dangerous, because you lack a way to see exactly what changed and to accept/reject such changes in a granular way.

The styler package can also be integrated with various platforms for hosting source code and doing continuous integration. For example, the tidyverse packages use a GitHub Action that restyles a package when triggered by a special comment (/style) on a pull request. This allows maintainers to focus on reviewing the substance of the pull request, without having to nitpick small issues of whitespace or indentation23 .

6.4 Understand when code is executed

Up until now, you’ve probably been writing scripts, R code saved in a file that you execute interactively, perhaps using an IDE and/or source(), or noninteractively via Rscript. There are two main differences between code in scripts and packages:

In a script, code is run … when you run it! The awkwardness of this statement reflects that it’s hard to even think about this issue with a script. However, we must, in order to appreciate that the code in a package is run when the package is built. This has big implications for how you write the code below

R/: package code should only create objects, the vast majority of which will be functions.Functions in your package will be used in situations that you didn’t imagine. This means your functions need to be thoughtful in the way that they interact with the outside world.

We expand on the first point here and the second in the next section. These topics are also illustrated concretely in Section 5.6.

When you source() a script, every line of code is executed and the results are immediately made available. Things are different with package code, because it is loaded in two steps. When the binary package is built (often, by CRAN) all the code in R/ is executed and the results are saved. When you attach a package with library(), these cached results are re-loaded and certain objects (mostly functions) are made available for your use. The full details on what it means for a package to be in binary form are given in Section 3.4. We refer to the creation of the binary package as (binary) “build time” and, specifically, we mean when R CMD INSTALL --build is run. (You might think that this is what R CMD build does, but that actually makes a bundled package, a.k.a. a “source tarball”.) For macOS and Windows users of CRAN packages, build time is whenever CRAN built the binary package for their OS. For those who install packages from source, build time is essentially when they (built and) installed the package.

Consider the assignment x <- Sys.time(). If you put this in a script, x tells you when the script was source()d. But if you put that same code at the top-level in a package, x tells you when the package binary was built. In Section 5.6, we show a complete example of this in the context of forming timestamps inside a package.

The main takeaway is this:

Any R code outside of a function is suspicious and should be carefully reviewed.

We explore a few real-world examples below that show how easy it is to get burned by this “build time vs. load time” issue. Luckily, once you diagnose this problem, it is generally not difficult to fix.

6.4.1 Example: A path returned by system.file()

The shinybootstrap2 package once had this code below R/:

dataTableDependency <- list(

htmlDependency(

"datatables", "1.10.2",

c(file = system.file("www/datatables", package = "shinybootstrap2")),

script = "js/jquery.dataTables.min.js"

),

htmlDependency(

"datatables-bootstrap", "1.10.2",

c(file = system.file("www/datatables", package = "shinybootstrap2")),

stylesheet = c("css/dataTables.bootstrap.css", "css/dataTables.extra.css"),

script = "js/dataTables.bootstrap.js"

)

)So dataTableDependency was a list object defined in top-level package code and its value was constructed from paths obtained via system.file(). As described in a GitHub issue,

This works fine when the package is built and tested on the same machine. However, if the package is built on one machine and then used on another (as is the case with CRAN binary packages), then this will fail – the dependency will point to the wrong directory on the host.

The heart of the solution is to make sure that system.file() is called from a function, at run time. Indeed, this fix was made here (in commit 138db47) and in a few other packages that had similar code and a related check was added in htmlDependency() itself. This particular problem would now be caught by R CMD check, due to changes that came with staged installation as of R 3.6.0.

6.4.2 Example: Available colours

The crayon package has a function, crayon::show_ansi_colors(), that displays an ANSI colour table on your screen, basically to show what sort of styling is possible. In an early version, the function looked something like this:

show_ansi_colors <- function(colors = num_colors()) {

if (colors < 8) {

cat("Colors are not supported")

} else if (colors < 256) {

cat(ansi_colors_8, sep = "")

invisible(ansi_colors_8)

} else {

cat(ansi_colors_256, sep = "")

invisible(ansi_colors_256)

}

}

ansi_colors_8 <- # code to generate a vector covering basic terminal colors

ansi_colors_256 <- # code to generate a vector covering 256 colorswhere ansi_colors_8 and ansi_colors_256 were character vectors exploring a certain set of colours, presumably styled via ANSI escapes.

The problem was those objects were formed and cached when the binary package was built. Since that often happens on a headless server, this likely happens under conditions where terminal colours might not be enabled or even available. Users of the installed package could still call show_ansi_colors() and num_colors() would detect the number of colours supported by their system (256 on most modern computers). But then an un-coloured object would print to screen (the original GitHub issue is r-lib/crayon#37).

The solution was to compute the display objects with a function at run time (in commit e2b368a:

show_ansi_colors <- function(colors = num_colors()) {

if (colors < 8) {

cat("Colors are not supported")

} else if (colors < 256) {

cat(ansi_colors_8(), sep = "")

invisible(ansi_colors_8())

} else {

cat(ansi_colors_256(), sep = "")

invisible(ansi_colors_256())

}

}

ansi_colors_8 <- function() {

# code to generate a vector covering basic terminal colors

}

ansi_colors_256 <- function() {

# code to generate a vector covering 256 colors

}Literally, the same code is used, it is simply pushed down into the body of a function taking no arguments (similar to the shinybootstrap2 example). Each reference to, e.g., the ansi_colors_8 object is replaced by a call to the ansi_colors_8() function.

The main takeaway is that functions that assess or expose the capabilities of your package on a user’s system must fully execute on your user’s system. It’s fairly easy to accidentally rely on results that were cached at build time, quite possibly on a different machine.

6.4.3 Example: Aliasing a function

One last example shows that, even if you are careful to only define functions below R/, there are still some subtleties to consider. Imagine that you want the function foo() in your package to basically be an alias for the function blah() from some other package, e.g. pkgB. You might be tempted to do this:

foo <- pkgB::blahHowever, this will cause foo() in your package to reflect the definition of pkgB::blah() at the version present on the machine where the binary package is built (often CRAN), at that moment in time. If a bug is discovered in pkgB::blah() and subsequently fixed, your package will still use the older, buggy version, until your package is rebuilt (often by CRAN) and your users upgrade, which is completely out of your control. This alternative approach protects you from this:

foo <- function(...) pkgB::blah(...)Now, when your user calls foo(), they are effectively calling pkgB::blah(), at the version installed on their machine at that very moment.

A real example of this affected an older version of knitr, related to how the default “evaluate” hook was being set to evaluate::evaluate() (original issue is yihui/knitr#1441, resolved in commit d6b53e0).

6.5 Respect the R landscape

Another big difference between a script and a package is that other people are going to use your package, and they’re going to use it in situations that you never imagined. This means you need to pay attention to the R landscape, which includes not just the available functions and objects, but all the global settings.

You have changed the R landscape if you’ve loaded a package with library(), or changed a global option with options(), or modified the working directory with setwd(). If the behaviour of other functions differs before and after running your function, you’ve modified the landscape. Section 5.7 has a concrete example of this involving time zones and the locale-specific printing of datetimes. Changing the landscape is bad because it makes code much harder to understand.

There are some functions that modify global settings that you should never use because there are better alternatives:

Don’t use

library()orrequire(). These modify the search path, affecting what functions are available from the global environment. Instead, you should use theDESCRIPTIONto specify your package’s requirements, as described in Chapter 9. This also makes sure those packages are installed when your package is installed.Never use

source()to load code from a file.source()modifies the current environment, inserting the results of executing the code. There is no reason to usesource()inside your package, i.e. in a file belowR/. Sometimes peoplesource()files belowR/during package development, but as we’ve explained in Section 4.4 and Section 6.2,load_all()is a much better way to load your current code for exploration. If you’re usingsource()to create a dataset, it is better to use the methods in Chapter 7 for including data in a package.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of other functions that should be used with caution:

options()par()setwd()Sys.setenv()Sys.setlocale()-

set.seed()(or anything that changes the state of the random number generator)

If you must use them, make sure to clean up after yourself. Below we show how to do this using functions from the withr package and in base R.

The flip side of this coin is that you should avoid relying on the user’s landscape, which might be different to yours. For example, functions that rely on sorting strings are dangerous, because sort order depends on the system locale. Below we see that locales one might actually encounter in practice (C, English, French, etc.) differ in how they sort non-ASCII strings or uppercase versus lowercase letters.

x <- c("bernard", "bérénice", "béatrice", "boris")

withr::with_locale(c(LC_COLLATE = "fr_FR"), sort(x))

#> [1] "béatrice" "bérénice" "bernard" "boris"

withr::with_locale(c(LC_COLLATE = "C"), sort(x))

#> [1] "bernard" "boris" "béatrice" "bérénice"

x <- c("a", "A", "B", "b", "A", "b")

withr::with_locale(c(LC_COLLATE = "en_CA"), sort(x))

#> [1] "a" "A" "A" "b" "b" "B"

withr::with_locale(c(LC_COLLATE = "C"), sort(x))

#> [1] "A" "A" "B" "a" "b" "b"If you write your functions as if all users have the same system locale as you, your code might fail.

6.5.1 Manage state with withr

If you need to modify the R landscape inside a function, then it is important to ensure your change is reversed on exit of that function. This is exactly what base::on.exit() is designed to do. You use on.exit() inside a function to register code to run later, that restores the landscape to its original state. It is important to note that proper tools, such as on.exit(), work even if we exit the function abnormally, i.e. due to an error. This is why it’s worth using the official methods described here over any do-it-yourself solution.

We usually manage state using the withr package, which provides a flexible, on.exit()-like toolkit (on.exit() itself is covered in the next section). withr::defer() can be used as a drop-in replacement for on.exit(). Why do we like withr so much? First, it offers many pre-built convenience functions for state changes that come up often. We also appreciate withr’s default stack-like behaviour (LIFO = last in, first out), its usability in interactive sessions, and its envir argument (in more advanced usage).

The general pattern is to capture the original state, schedule its eventual restoration “on exit”, then make the state change. Some setters, such as options() or par(), return the old value when you provide a new value, leading to usage that looks like this:

Certain state changes, such as modifying session options, come up so often that withr offers pre-made helpers. Table 6.2 shows a few of the state change helpers in withr that you are most likely to find useful:

| Do / undo this | withr functions |

|---|---|

| Set an R option |

with_options(), local_options()

|

| Set an environment variable |

with_envvar(), local_envvar()

|

| Change working directory |

with_dir(), local_dir()

|

| Set a graphics parameter |

with_par(), local_par()

|

You’ll notice each helper comes in two forms that are useful in different situations:

-

with_*()functions are best for executing small snippets of code with a temporarily modified state. (These functions are inspired by howbase::with()works.)f <- function(x, sig_digits) { # imagine lots of code here withr::with_options( list(digits = sig_digits), print(x) ) # ... and a lot more code here } -

local_*()functions are best for modifying state “from now until the function exits”.g <- function(x, sig_digits) { withr::local_options(list(digits = sig_digits)) print(x) # imagine lots of code here }

Developing code interactively with withr is pleasant, because deferred actions can be scheduled even on the global environment. Those cleanup actions can then be executed with withr::deferred_run() or cleared without execution with withr::deferred_clear(). Without this feature, it can be tricky to experiment with code that needs cleanup “on exit”, because it behaves so differently when executed in the console versus at arm’s length inside a function.

More in-depth coverage is given in the withr vignette Changing and restoring state and withr will also prove useful when we talk about testing in Chapter 13.

6.5.2 Restore state with base::on.exit()

Here is how the general “save, schedule restoration, change” pattern looks when using base::on.exit().

Other state changes aren’t available with that sort of setter and you must implement it yourself.

g <- function(a, b, c) {

...

scratch_file <- tempfile()

on.exit(unlink(scratch_file), add = TRUE)

file.create(scratch_file)

...

}Note that we specify on.exit(..., add = TRUE), because you almost always want this behaviour, i.e. to add to the list of deferred cleanup tasks rather than to replace them entirely. This (and the default value of after) are related to our preference for withr::defer(), when we’re willing to take a dependency on withr. These issues are explored in a withr vignette.

6.5.3 Isolate side effects

Creating plots and printing output to the console are two other ways of affecting the global R environment. Often you can’t avoid these (because they’re important!) but it’s good practice to isolate them in functions that only produce output. This also makes it easier for other people to repurpose your work for new uses. For example, if you separate data preparation and plotting into two functions, others can use your data prep work (which is often the hardest part!) to create new visualisations.

6.5.4 When you do need side-effects

Occasionally, packages do need side-effects. This is most common if your package talks to an external system — you might need to do some initial setup when the package loads. To do that, you can use two special functions: .onLoad() and .onAttach(). These are called when the package is loaded and attached. You’ll learn about the distinction between the two in Section 10.4. For now, you should always use .onLoad() unless explicitly directed otherwise.

Some common uses of .onLoad() and .onAttach() are:

-

To set custom options for your package with

options(). To avoid conflicts with other packages, ensure that you prefix option names with the name of your package. Also be careful not to override options that the user has already set. Here’s a (highly redacted) version of dplyr’s.onLoad()function which sets an option that controls progress reporting:This allows functions in dplyr to use

getOption("dplyr.show_progress")to determine whether to show progress bars, relying on the fact that a sensible default value has already been set.

-

To display an informative message when the package is attached. This might make usage conditions clear or display package capabilities based on current system conditions. Startup messages are one place where you should use

.onAttach()instead of.onLoad(). To display startup messages, always usepackageStartupMessage(), and notmessage(). (This allowssuppressPackageStartupMessages()to selectively suppress package startup messages)..onAttach <- function(libname, pkgname) { packageStartupMessage("Welcome to my package") }

As you can see in the examples, .onLoad() and .onAttach() are called with two arguments: libname and pkgname. They’re rarely used (they’re a holdover from the days when you needed to use library.dynam() to load compiled code). They give the path where the package is installed (the “library”), and the name of the package.

If you use .onLoad(), consider using .onUnload() to clean up any side effects. By convention, .onLoad() and friends are usually saved in a file called R/zzz.R. (Note that .First.lib() and .Last.lib() are old versions of .onLoad() and .onUnload() and should no longer be used.)

One especially hairy thing to do in a function like .onLoad() or .onAttach() is to change the state of the random number generator. Once upon a time, ggplot2 used sample() when deciding whether to show a startup message, but only in interactive sessions. This, in turn, created a reproducibility puzzle for users who were using set.seed() for their own purposes, prior to attaching ggplot2 with library(ggplot2), and running the code both interactively and noninteractively. The chosen solution was to wrap the offending startup code inside withr::with_preserve_seed(), which leaves the user’s random seed as it found it.

6.6 Constant health checks

Here is a typical sequence of calls when using devtools for package development:

- Edit one or more files below

R/. -

document()(if you’ve made any changes that impact help files or NAMESPACE) load_all()- Run some examples interactively.

-

test()(ortest_active_file()) check()

An interesting question is how frequently and rapidly you move through this development cycle. We often find ourselves running through the above sequence several times in an hour or in a day while adding or modifying a single function.

Those newer to package development might be most comfortable slinging R code and much less comfortable writing and compiling documentation, simulating package build & installation, testing, and running R CMD check. And it is human nature to embrace the familiar and postpone the unfamiliar. This often leads to a dysfunctional workflow where the full sequence above unfolds infrequently, maybe once per month or every couple of months, very slowly and often with great pain:

- Edit one or more files below

R/. - Build, install, and use the package. Iterate occasionally with previous step.

- Write documentation (once the code is “done”).

- Write tests (once the code is “done”).

- Run

R CMD checkright before submitting to CRAN or releasing in some other way.

We’ve already talked about the value of fast feedback, in the context of load_all(). But this also applies to running document(), test(), and check(). There are defects you just can’t detect from using load_all() and running a few interactive examples that are immediately revealed by more formal checks. Finding and fixing 5 bugs, one at a time, right after you created each one is much easier than troubleshooting all 5 at once (possibly interacting with each other), weeks or months after you last touched the code.

If you’re planning on submitting your package to CRAN, you must use only ASCII characters in your .R files. In practice, this means you are limited to the digits 0 to 9, lowercase letters ‘a’ to ‘z’, uppercase letters ‘A’ to ‘Z’, and common punctuation.

But sometimes you need to inline a small bit of character data that includes, e.g., a Greek letter (µ), an accented character (ü), or a symbol (30°). You can use any Unicode character as long as you specify it in the special Unicode escape "\u1234" format. The easiest way to find the correct code point is to use stringi::stri_escape_unicode():

x <- "This is a bullet •"

y <- "This is a bullet \u2022"

identical(x, y)

#> [1] TRUE

cat(stringi::stri_escape_unicode(x))

#> This is a bullet \u2022Sometimes you have the opposite problem. You don’t intentionally have any non-ASCII characters in your R code, but automated checks reveal that you do.

W checking R files for non-ASCII characters ...

Found the following file with non-ASCII characters:

foo.R

Portable packages must use only ASCII characters in their R code,

except perhaps in comments.

Use \uxxxx escapes for other characters.The most common offenders are “curly” or “smart” single and double quotes that sneak in through copy/paste. The functions tools::showNonASCII() and tools::showNonASCIIfile(file) help you find the offending file(s) and line(s).

tools::showNonASCIIfile("R/foo.R")

#> 666: #' If you<e2><80><99>ve copy/pasted quotes, watch out!Unfortunately you can’t use subdirectories inside

R/. The next best thing is to use a common prefix, e.g.,abc-*.R, to signal that a group of files are related.↩︎See the Commands workflow in the GitHub Actions for the R language repository.↩︎

The Robot Pedantry, Human Empathy blog post by Mike McQuaid does an excellent job summarizing the benefit of automating tasks like code re-styling.↩︎